05 Jun 2023

- Financial Services

Testing consumer understanding

Two weeks ago, my colleague and namesake Stu Charlton hosted a webinar about the Consumer Duty. When he came to the end we expected a broad range of questions around the topics covered. But one area dominated: the consumer understanding outcome.

-

Stuart Tayler

Practice Director

How to use qualitative research to address a key Consumer Duty outcome.

Consumer understanding

For those that haven’t pored over section 2A.5 of the Consumer Duty or chapter 8 of the non-Handbook guidance,”Consumer understanding” is one of four outcomes that the FCA expects firms to deliver. It says that firms should:

support their customers by helping them make informed decisions about financial products and services.

We want customers to be given the information they need, at the right time, and presented in a way they can understand. This is an integral part of firms creating an environment in which customers can pursue their financial objectives.

The guidance goes on to state that firms should:

test communications where appropriate [and check that] customers can make effective decisions and act in their interests

Herein lies our attendees’ problem: they need to test for comprehension, but they don’t know how.

The guidance does actually provide examples of research methods to test understanding: randomised controlled trials, A/B tests, surveys, interviews and focus groups. But, I believe the questions that followed our webinar suggest that many firms aren’t sure how to apply those methods. It’s like being given the option of using a car, a motorbike, or bicycle to get to a destination, without knowing how to drive, ride or cycle.

Perhaps a story from one of our recent projects will give you an idea of how to apply one of those methods: interviews.

Watch the webinar

Part 1: How to test for Consumer Understanding

21 May 2025 Online event

-

Stuart Tayler

CXPartners

Stuart Tayler

-

Stu Charlton

CXPartners

Stu Charlton

Our challenge

Late last year, a new piece of regulation (unrelated to the Consumer Duty) was about to affect one of our financial services clients.

It required the firm to report back specific data on how people were using one of their products. So they asked us to design a digital form to send to customers to ask them.

Consumer understanding was vital: if people didn’t understand what they were being asked for, and why, they would ignore the firm’s request. And, if people couldn’t answer some of the complex, but necessary, financial questions, they would be locked out of their account.

The FCA had set a looming deadline for this data to be reported. So, before the firm pushed thousands of customers towards the form, they needed to feel confident it would work. With that in mind, we decided interviews would be the most efficient method.

How we tested comprehension

We created a prototype of the journey and asked representative users to run through it and complete the form. So far, this process will seem familiar if you’ve observed any usability testing.

But to test comprehension we did two specific things.

Firstly, during the journey we carefully observed participants’:

- verbal cues e.g. “I’m confused”

- utterances e.g.“err”

- and non-verbal cues e.g frowning.

Secondly, we asked a structured set of questions at the end of the task. We asked people to explain back to us certain things they had seen, for example, the definition of a financial product, or who is eligible for it.

By asking people to explain concepts in their own words, we can assess comprehension through observing:

- Can they explain the concept?

- Is the explanation right?

- How confident are they?

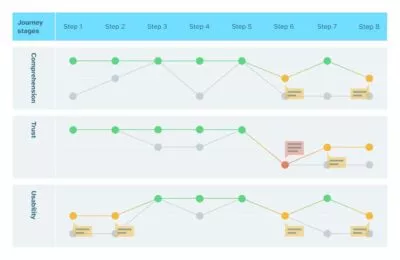

The data from these two activities allowed us to then rate the participant’s comprehension at each point in the user journey. This is a subjective assessment and so two researchers completed the ratings to make them more reliable.

We then mapped comprehension levels against the user journey. In this case we also mapped other subjective assessments: trust and usability.

Here is a version of that map (with details removed):

An assessment of comprehension is only a means to an end – to make things easier to understand. So, we used our research findings to make changes to the form before testing it again, and then again.

Here is the same map after a second round of research:

Using this iterative approach, our comprehension scores became relative (are we improving comprehension or not?) rather than absolute (level 2 or 3). That means questions about the validity of a subjective rating become less relevant.

This approach to testing comprehension meant we could:

- Pinpoint comprehension failures in the customer journey

- Track changes over design iterations

- Credibly demonstrate that the firm was attentive to consumer understanding: both benchmarking it and taking action to improve it

But the most important outcome is that we improved comprehension for the people that had to use this form.

Moreover, it had benefits to the firm: they had higher response rates than similar initiatives, and fewer support calls – saving them money.

It’s a great example of the type of win-win results you get from designing in a user-centred way, and why the Consumer Duty can be an opportunity for firms.

Other ways to test for consumer understanding

The story above shows one way to assess comprehension, but there are more to choose from:

- Exam-type questions. You ask these questions in a one-to-one interview after the participant has finished a task.

- Annotation. You ask users to highlight what sentences they find hard to understand.

- Eye-tracking. Data from these studies shows where people are re-reading words or taking longer to read, revealing your problem passages.

- Survey. You ask exam-type questions again, but at a larger scale. This is useful if you want to compare some new vs old content and get some quantitative evidence.

Combining methods will give you a more robust view of where people aren’t understanding what you’re telling them. But the mixture of different methods will depend on a range of factors: the size of your organisation (and so resources available), deadlines, budgets, whether you are testing existing or new content – and perhaps the most important factor – the risk of harm to someone if they don’t understand.

If you’re not sure where to start, we can help you to work out what comprehension assessment plan you need to put in place. Get in touch.