09 Jul 2021

Researching sensitive topics with people in vulnerable situations

Some useful tips for building confidence and being better prepared when setting up research around sensitive topics with people in vulnerable situations.

Last week my colleague, Amy Bracewell, and I ran a webinar, “Research around sensitive topics with people in vulnerable situations” based on projects we had done with Women’s Aid, Samaritans, Talk to Frank, and NHS England and Improvement. We have researched domestic abuse, drug use, traumas and living with severe mental illnesses (SMI).

UX research requires us, researchers and designers, to speak with a range of individuals to learn about their world and behaviours. These topics can vary from light (personal consumption preferences) to heavy (abuse, suicide, homelessness etc). How do we respond when someone shares their past traumas with us? Sadly, the reality is that sensitive topics such as suicide come up quite a lot when you’re working in the mental health space. As researchers listening on the other side, it’s easy to feel underprepared and overwhelmed.

In the beginning, I felt anxious and unprepared for the conversations I’d be engaging in. I had imposter syndrome and didn’t feel qualified to talk about such hard and personal stories.

The key to easing anxiety is to be prepared. We looked to earlier projects, led by our previous research director, with Women’s Aid for guidance.

Here are some things we did that helped to build our confidence and be better prepared when setting up these research sessions:

- Establish trust with your research participants

- Getting the language right

- Include champions

- Have support available

Establishing trust

Before Covid, we conducted Women’s Aid research from our Bristol office labs.

We did a rearrangement of our office space so that it felt safe and comfortable for the women who had agreed to take part. We stopped people walking past the research room, made sure tea and biscuits were available and made the room feel less like an interview room. The adjustments in the space helped to create a feeling of trust where participants could talk to us openly about their experiences.

We’ve kept it like this ever since and it puts everyone, not just our vulnerable participants, at ease!

With everything being remote, we couldn’t replicate that safety of the physical space but hoped participants may be more comfortable in their familiar environments, with greater control over their surroundings.

We arranged check-in calls the day before the research session to make sure participants would know what to expect and address any concerns. Often, it was their first time participating in research and setting the expectations and reassuring them helped build trust. It also acted as an opportunity for the participants to get familiar with us and our voice. We had positive feedback from making these calls (as soon as they realised it’s not spam!).

Getting the language right

I recall interviewing a man diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder. He hated being associated with the illness and refused to take the medications and get support. He believed with his determination and strong mindset he could will the illness away. As much as I believe mindset is a powerful thing and is inevitably linked to one’s physical condition, I know the illness he has can’t be cured in this manner. But it shows how much he did not want to be associated with having this illness and be treated differently.

Identity matters. So we need to respect that and ensure the language we use does not confine people to labels. We might have complicated life or health situations but they do not define us.

Include champions

In addition to working with subject matter experts, we also leaned on change-makers.

When we worked with Women’s Aid, we invited community champion ambassadors and Women’s Aid staff to help shape our research process. It was a truly collaborative effort. This meant the research techniques we employed not only reflected our clients’ objectives but we could be sure we were interviewing appropriately for the women participants too.

For the NHS project, we ran a pilot session with a participant ahead of the scheduled research days and got their help in shaping the research structure and questions. We made our intentions clear and they helped shape the research process so the flow of the sessions would feel right.

Have support available

We have a clear duty of care to those who participate in our research and agree to share their stories with us. Therefore, we always provide aftercare to participants. This was especially valuable to the women who took part in our Women’s Aid research. Although we ask our questions sensitively, we have to understand that our sessions could evoke trauma for many. We always had a dedicated Women’s Aid support worker contact who was available to provide support as and when any of the participants felt they needed it after the sessions.

For Talk to Frank and Samaritans, we also shared a debrief sheet at the end of each session with the participants where they could get additional support. It’s about continuity and making sure that our participants know that there is help available after sessions, rather than leaving them with a thank you and goodbye.

What we learned from our research

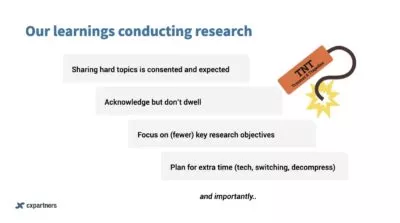

The testing days can feel quite full-on especially if you have back to back sessions. We learnt that our initial reservations and concerns at the beginning of the project were unfounded.

We found that:

- Sharing hard topics is consented to and expected Since they agreed to participate in the research, people are willing to share their life stories, however difficult, as they feel they’re contributing and helping others by participating. They’re motivated.

- Acknowledge but don’t dwell We also learnt that it can be hard to move on to the next question or follow up when you get hit with an experience T&T bomb (traumas & tragedies). Such bombs I heard included abuse, multiple suicide attempts and the loss of family. It can freeze you on the spot, especially if you haven’t had a similar experience. But a notable healthcare professional who, for decades, had championed better care for people with severe mental illness reminded me that:

It’s a privilege that this person is sharing their deeply personal experiences with you.

The best thing to do is take their experiences and stories to transform services and products better. She’s so wise. We need to acknowledge their personal stories and situations but also not dwell too much and risk reopening wounds.

- Focus on (fewer) key research objectives It’s easy to run over if the research is unstructured, so try having fewer focus areas that give room for organic conversations. Then you’ll get the right level of depth for findings.

- Always plan for extra time Allow more time for sessions and in between sessions. You need to reset from one story to another. If you’re conducting the research remotely, be prepared to encounter tech issues. Always have a phone backup option for the sessions which can come in handy when experiencing issues with remote research platforms.

and more importantly..

Safeguarding for researchers

In doing these projects, I did some research around the topic of self-care for UX. I came across terminology like “compassion fatigue”, “burnout” and “vicarious trauma.” Phrases that describe the emotional and physical impact of being too close to your users’ pain points and problems. And realised this is a thing!

Not many researchers have the necessary skills and knowledge to recognise their own vulnerable states, how to protect themselves and their wellbeing. Janice Hannaway and Jane Reid wrote a great article on self-care for researchers, they mentioned that “not only do user researchers hear similar content to that of a therapist but due to the nature of the agile environment, they will also hear it repeatedly…However, the main difference is that, unlike user researchers, therapists are safeguarded with regular clinical supervision.”

Conducting research appropriately and considerably is one challenge, once the analysis and the synthesising begins, we have another challenge. That is to turn the research insights into something tangible that the team can take away from.

Hearing these hard-lived stories, it’s difficult to not feel attached or feel an extra sense of responsibility to spread these stories and turn their experiences as fuel to improve services for the better. Often the depth of the research we do is in our heads. Solely relying on a pdf research report doesn’t quite convey the richness of the findings.

Visual storytelling

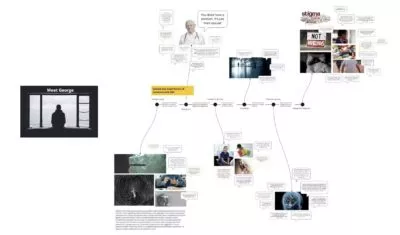

While empathy maps and personas are great to gain deeper insight into our target audiences, they still don’t quite bring their stories alive. I can’t help but feel that they only scratch the surface of highlighting the richness of these personal stories.

So I started thinking: Can we take it further?

I thought about this on the NHS project after speaking with numerous people with severe mental illness. I kept thinking about the personal stories and journeys I hear about but not well articulated in the confines of a research deck.

So I played around with depicting a visual journey on the online whiteboard platform Miro and ran it through with the team. The result is an amalgamation of all the experiences I heard into a one-person journey in a linear approach. This visual timeline highlights key stages where people with severe mental illness would be more at risk or vulnerable and how their conditions change while receiving support (or lack off) from the NHS. It’d highlight all the things that could go wrong, the anxieties that rise and traumas that get triggered at each stage. The goal is to use storytelling to make their lived experiences stick to the team members who can really make a difference.

The Timeline wasn’t a deliverable but I felt the need to do it and tell the story in a different way than the large research pdf report and empathy maps I’ve done previously.

To recap

Key things to keep in mind when researching around sensitive topics with people in vulnerable situations:

- Safeguard participants: It is crucial to keep the participants’ wellbeing front of mind. It’s essential that you prepare well for this — create a safe space, focus on creating an environment of trust, lean on the expert knowledge you have in the room and make sure you have support available to offer to your participants.

- Safeguard researchers: This is just as important. Do keep a check on yourselves as researchers — set your boundaries, make sure you have a network of people who can support you and leave yourself plenty of time to decompress afterwards.

- Leverage storytelling: Use the power of narrative and storytelling to engage the team and empower them to carry on the stories and insights to improve services for the better. Explore visual journeys, illustrations, comics, videos, whatever way to get your team to absorb the insights.

- Keep learning and iterating: This is a no brainer. As with learning every skill, there is always room for improvement. The output of your work can positively impact these individuals’ lives. You should feel proud and privileged to be able to make a difference. Keep fighting the good fight. And let’s continue to learn from each other.

And that’s a wrap!