Reflexive Research: 5 tips to minimise bias

Quite a few years ago, I wrote an article about using ‘reflexive thinking’ to avoid bias in user research. This topic feels as relevant as ever, so I’ve dug it out of the vaults and given it a polish to share with you today.

‘Reflexivity’ is a research concept that stems from anthropology - the study of people and their behaviour patterns. But it’s applicable to all kinds of research.

It’s likely that you’re already thinking reflexively without realising it.

In this article, I explain what it is, why it’s important and how to get more out of it.

What is reflexivity?

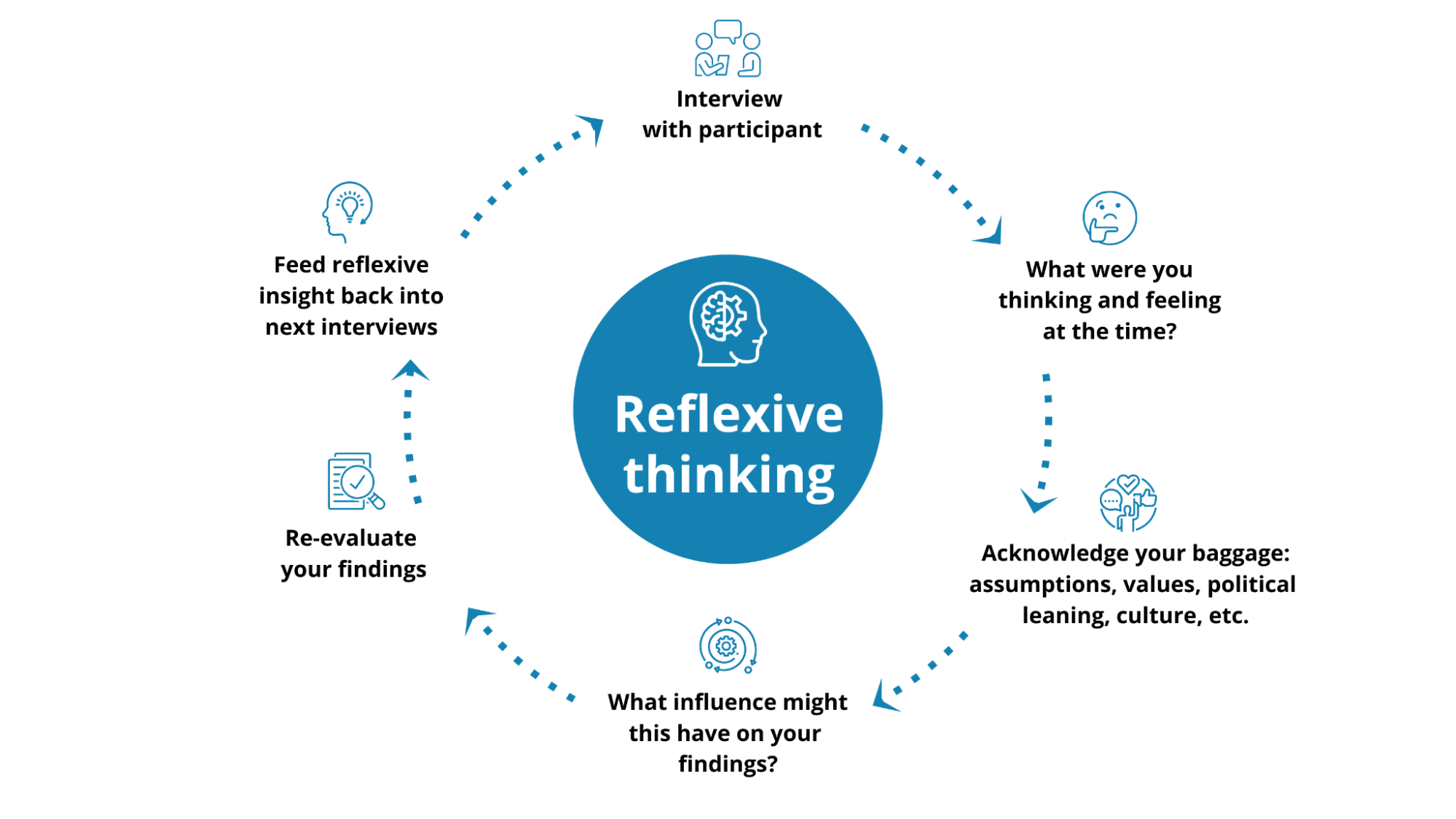

Being reflexive means researchers take the time to examine their assumptions and preconceptions before carrying out research. This allows them to recognise how their views may unconsciously shape the study.

The truth is none of us are detached, objective observers. As human beings, we all have opinions and pre-formulated ideas based on our experiences and upbringing. Our worldviews are based on our thought patterns, personal values, political leanings, culture, ethnicity, religion, age, gender, and job.

The goal of reflexivity is not to remove biases - that would be impossible. It’s about being transparent and understanding how biases may influence our research. With more self-awareness, studies can account for subjective inputs.

How does this affect UX research?

It’s easy to forget about our influence on the process of research. However, our preconceptions can impact decisions - for instance, what questions we ask and how we word them or what we emphasise in our notes.

By thinking reflexively throughout the entire research process - by reflecting on ourselves and making the research process itself a point of analysis - we reduce the risk of being misled by our own experiences and interpretations.

Example: During a project about an emotive subject like caring for elderly parents, the researcher projects their own feelings into the interview - how they would feel if they were in the same situation.

However, their relationship with their parents will be unique and, therefore, different from the participant’s.

The researcher’s reaction to the participant’s answers may influence what questions they ask next and how they ask them, affecting the answers given.

Or, the researcher’s feelings towards their parents may influence what they emphasise in the findings report - for example, guilt, regret or resentment.

If the researcher reflects on this and recognises it, they can mitigate its influence on the following interviews, the report or the rest of the project.

How can we be more reflexive in UX?

Here are five practical ways that you can incorporate reflexivity into your research process:

1. Make user interviews a team sport

Always involve at least two UX practitioners in an interview, and have more team members - including the client - listen to the interview as it’s taking place. Allow a gap between interviews for a team discussion and encourage critical reflection on the interview.

It’s not about asking someone else to ‘confirm’ that one person’s take on the findings is ‘correct’. Rather, it helps the researcher look at things from angles that may have been overlooked or dismissed without taking the time to consider them thoroughly.

Example: A participant is describing what their job involves. What they describe sounds confusing and stressful to the researcher.

The researcher interprets it this way because they have no prior knowledge of that job, and it’s very different from anything they have experienced. They assume that the participant must also find their job confusing and stressful.

If the researcher discusses this with colleagues, it may come to light that this is not what the participant was describing at all. What they actually meant was that they enjoyed the challenge of their job.

2. Consider your reaction towards unexpected responses

When you don’t get the expected response from a participant, it reveals your assumptions and preconceptions. Use these experiences to reflect on any preconceived ideas you brought into the interview.

Keep this in mind for following interviews to avoid making the same presumptions going forward.

Example: The researcher shows the participant a design that forces them to step through a series of add-ons and answer yes or no. The client has requested this feature.

The researcher expects that this will annoy the participant. However, the participant doesn’t react in this way at all.

The researcher reflects on this and acknowledges the assumption they’d made. They can then use this experience in the following interviews to prevent making similar speculations.

3. Keep a diary of how you’re feeling during research

Reflect on your emotional state and what happened that day, and note it in a diary. When you write up the findings, refer to it to help you make allowances for how you felt.

Keeping a diary is particularly useful if you’re conducting research independently and haven’t been able to discuss the interviews with a colleague.

Example: The researcher argues with their partner before coming to work. The tension they’re experiencing when conducting the interview might affect how they ask questions and interpret answers.

They note this in a diary and refer to it when writing up the findings. As a result, they can consider their feelings and adjust their interpretation of what they heard if necessary.

4. Watch a recording of yourself carrying out an interview

Choose a recording where you can see your whole body and your facial expressions.

With a colleague, watch the recording. Both make notes on how you, the interviewer, are coming across.

Consider what you say, how you say it and what your body language and facial expressions convey.

Afterwards, discuss the notes you made. What can be most interesting is when you disagree.

Use the insight from this exercise to inform your interview technique going forward.

Example: The researcher unintentionally makes overly sympathetic facial expressions and noises when the participant tells them about a negative experience with the product they’re testing.

The consequence might be that the participant takes this as an encouragement to focus on the negative experience more than they would have otherwise.

Without knowing that they were making overly sympathetic facial expressions and noises, the researcher might assume the participant was preoccupied with the experience they were discussing. But in fact, the participant was just doing what they thought the researcher wanted.

5. Consider how your life experiences may influence what you document

When writing the findings report, reflect on your interpretation of the interview. How might your experiences in life so far influence what you choose to document?

Example: When writing the report, the researcher remembers feeling sorry for a participant because of some hardship they described.

They reflect on their own life, which is relatively privileged, and are careful not to over-emphasise the powerlessness of the participant.

Rather than requiring a drastic change to the research process, reflexivity is a subtle readjustment to your self-awareness that can make a profound difference to what you get out of your research.

If you’ve got any more tips for reflexive thinking, or if you have any anecdotes from situations where reflexive thinking has improved your research, I’d love to hear them. Drop me a line - anna.boscoe@cxpartners.co.uk

Further resources:

A Process of Reflection - Lives & Legacies: A Guide to Qualitative Interviewing http://www.utsc.utoronto.ca/~pchsiung/LAL/reflexivity

Subjectivity and Reflexivity in Qualitative Research—The FQS Issues http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/696/1504