User Research Myth Busting

A massive thanks to Emma Howell, our wonderful Research Lead and co-author of Researching UX : User Research who authored this article with me.

Over the years, we’ve heard many reasons why people don’t do research and these myths can perpetuate within organisations.

We feel it’s time for a bit of myth-busting to help you make sure user research happens on your own projects.

“We don’t have any time or budget to do any user research”

This flags a bigger issue, of course, that the value of research is not apparent enough for it to be included. The good news is that research doesn’t have to be hugely time consuming and can scale to suit the constraints of your project.

In reality, you can’t afford to leave user research out of your projects.You can be almost certain that you’ll make something that people can’t use and don’t need.

“You won’t learn anything from speaking to so few people”

You’ll be amazed at just how much you will learn from a relatively small group of people. We’ve frequently seen, just a days worth of research (typically five interviews) generate more work than has been possible for design and development teams to take on.

Ideally, you’ll be able to do regular testing as your design evolves. This isn’t always possible for smaller projects where you may have just one round of user research. This is still hugely valuable and worthwhile.

When conducting qualitative research, you’re not looking for proof, you’re looking for direction. If you need proof and validation you will want to consider quantitative too. Qualitative research will allow you to spot trends and patterns in behaviour that will help you to develop your ideas and thinking.

A pragmatic approach is to do enough research to allow you to make design decisions or pick a direction. A ‘little and often’ approach to research is a healthy position to take in order to continually improve your product.

“I’ve worked in this game for years, I know my customers better than anyone”

It stands to reason that no-one will know more about your customers than your customers themselves. It is definitely the case that people who have regular customer interactions - such as contact centre staff and sales people - know a lot about customer needs, and are well worth speaking to when you struggle to get to actual end users.

In reality, no one has any real idea how people will react to new products and services. It’s all a bit of an experiment until you get the thing in the hands of the people that it’s been designed for. Your research will add to the knowledge they have, and you’re also very likely to surprise them with interesting new insights about their customers.

“Customers don’t know what they want so what’s the point in asking them?”

In this scenario, expect to hear someone in a meeting mention something like “if we’d asked people what they wanted they would have said faster horses” as a reason to not conduct research to inform product innovation.

A common misconception is that user research involves asking people what they want, and for them to come up with amazing ideas for new products and services. This simply isn’t the case. Design research involves trying to find out what people need and whether the thing you are making is going to be useful and usable.

Innovative ideas come from design research because design teams get to understand what people really need, and critically, how these needs are either being or not being met by existing services. Research helps you to spot gaps and come up with ideas that feel worth pursuing because they directly address an observed need. A faster horse may well have got customers to places more quickly, but it wouldn’t have led to the heated seats and boot space we enjoy now.

“Research is for researchers and not compatible with business and strategy”

Research is a team sport which means it’s not just for researchers to get involved. Stakeholders from elsewhere should get involved too. If everyone has the chance to be involved, they will buy into your research. They will feel invested and have a deeper understanding of your findings. And that means you are more likely to see action off the back of your research.

Research, when conducted effectively, should be the foundation of decision making in business and should be used to inform business strategy. People from various parts of the organisation should observe research and see how and where their products and services are failing to meet the needs of their customers.

Good design researchers are able to articulate their findings and insights in ways that business people understand, bridging the gap between these different worlds. This is one of the key skills you need to be an effective UX’er - it’s about being able to translate what you are seeing into a design that solves the problem and being able to justify your design decisions in a language that the business will understand.

“We’ve got enough to be getting on with without more stuff to do from research.”

The irony here is that people are very good at being busy working on the wrong things. Research helps you to focus your efforts on the most important things that will yield the best outcomes for your customers and your organisation.

“We won’t be able to demonstrate the value of the investment in research quickly enough to justify it”

It’s surprising how quickly you start learning as soon as you start researching and talking to users. And what’s to stop you from making small changes based on what you learn straight away? Immediate value!

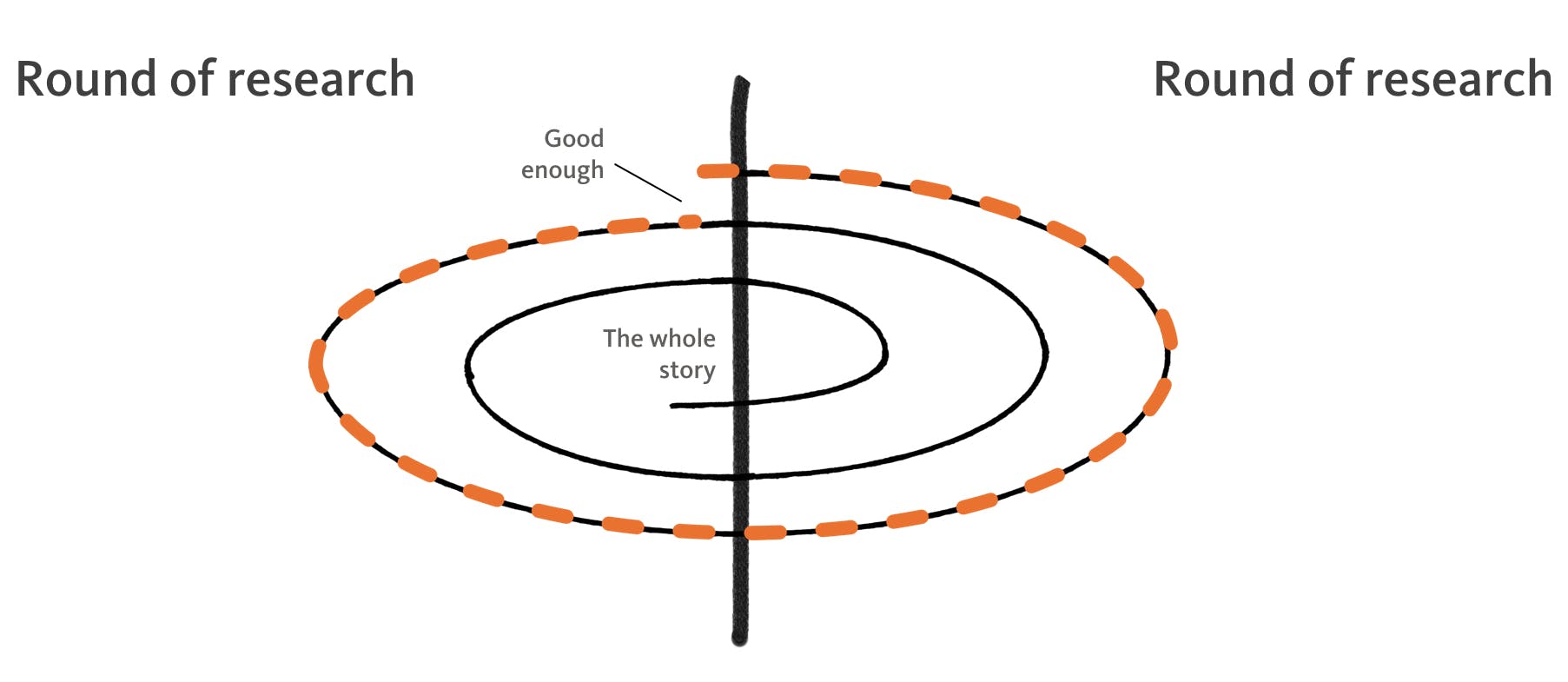

When planning user research, it’s worth thinking about when is enough research is good enough. Kristy Blazo from U1 Group describes the cycle of qualitative and quantitative research as a spiral. We’re adapted her research spiral slightly to think about rounds of research.

Each chunk of research builds on the last. The idea is that businesses should work around the spiral until it is no longer cost effective to do further research. This will be different for every project depending on the objectives and budget that you have. You can read more about this in the book Emma co-authored: ‘Researching UX: User Research’.

“Our project is secret. We can’t show it to people before we launch.”

There are practical steps you can take here to mitigate any perceived risk such as asking respondents to sign NDA’s and removing any identifiable elements within prototypes such as branding etc.

In reality, most commercial design projects will have some sensitivity in this area, so it’s familiar territory. We usually counter this concern by asking which poses the greatest risk: showing it to people and risking someone you conduct research with having the ability to launch a competitor or keeping it under wraps and hoping it works? Generally they favour the lower risk surrounding the former .

“I’m not interested in qualitative research, it’s just opinions afterall. Give me quantitative every day.”

Typically when organisations rely purely on quantitative research they manage to optimise a version of their product but have no clear idea of why it works. This means they are fearful of changing any aspect of it. You end up at a point where you hit the limits of your design and lose out on the insights you get from qualitative approaches which can uncover completely different ways of solving your design problems.

Quantitative research will tell you what. Qualitative will tell you why.

We really enjoy projects where clients have embraced both qualitative and quantitative methods. They’re hugely complementary and powerful when used properly together. One project comes to mind where a client had identified the most ‘successful’ design by way of multi-variant testing which we then investigated via qualitative methods to determine why it was so successful. Our insights gave our client a clear idea of why it works so that they could subsequently improve it without compromising its strengths.

“I’m not allowed to do any more research because a senior stakeholder is worried that if we find out what we’ve made isn’t any good it’ll make us look bad.”

It’s better to find out the things that aren’t quite right sooner rather than later. If you’re in the process of designing and building something, you can iterate and address the problems that you hear about. If you are testing something that already exists, research will give you direction and focus on what to do next.

Stakeholders sticking their head in the sand isn’t going to stop a problem being a problem. The quicker they’re spotted, the quicker they can be fixed. Besides, design is never finished and should be thought of as something that should be continually refined and improved. Nothing will ever be 100% perfect and shifting business priorities will always mean it’ll need to be re-focussed over time.

“Don’t you know the answer already? I thought you were a UX expert?!”

UX experts are really good at finding out about why something may or may not meet the needs of the people that it was designed for and then coming up with great ideas to address any shortcomings of the design.

Sometimes it feels like our expertise is confused with our ability to be able to comprehensively second guess the problems that people may have when they come to use something.

An expert review can be a useful starting point to start evaluating something from a users point of view, but should never be seen as a replacement for actual primary research.

Final thoughts

It can feel awkward having these conversations and difficult having to justify the value of your research.

We hope that you find these myths and tips helpful with the conversations that you’re having and make it a little easier.

If you have any tips, we’d love to hear them in the comment below.