How stories shape our choices and create impact

The big lie

At 9:32 am on 16 July 1969 the engines of Apollo 11's Saturn V rocket ignited and 2,950 tonnes of spacecraft lifted off from launch pad 39A.

Simultaneously, astronauts Michael Collins, Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin, and Neil Armstrong made their way to a secret bunker underneath the Florida launch site.

Over the next eight days, they were filmed on meticulously created sets as they pretended to carry out a daring space mission.

In fact, they were conducting one of the most elaborate, and devious hoaxes in human history.

It was a hoax designed to convince the Soviet Union of the superiority of American technology and demoralise it into believing it could never win the arms race.

The conspiracy theory is nonsense, of course. But over the past 50 years, that is the version consistently believed by around six percent of the US population.

This persists despite the fact that Chinese, Indian, and Japanese lunar missions have independently verified the landing sites.

Why is it that cold hard facts are sometimes no match for a good story?

Facts aren’t everything

We should worry about that. As design researchers, our first job is to collect facts. We work on the assumption that facts are valuable, that facts change minds, that facts have impact.

But facts aren’t everything. We’ve all been in situations where facts have been ignored or overruled.

Burying the truth

A colleague of mine once handed over a damning user research report to the Chief Operating Officer of a very large firm. She was about to waste millions on a project that would damage her firm’s user experience.

She thanked him, put the report in a drawer, and said that she would not be circulating it.

Have you ever had that feeling of impotent rage? How could they be so stupid? Couldn’t they see? What about the facts?

Just the facts

You’re not the only one. In the early ’90s Stephen Denning was working for the World Bank, trying to get support for a knowledge management programme - a new idea back then.

Denning put together plans, assembled his evidence and took it to his stakeholders.

He was met with a mixture of polite interest and indifference.

What he had was interesting, they said, and there was certainly potential - but the stakeholders still had questions. Perhaps he could provide more detail?

Which he did. And when he took it to his stakeholders, the cycle continued.

The springboard story

Then in 1996, he took a different approach: he started telling this story.

In June of last year, a health worker in a tiny town in Zambia went to the Web site of the Centers for Disease Control and got the answer to a question about the treatment of malaria.

It’s Zambia, one of the poorest countries in the world [and 1996, when Internet access was a novelty], and this happened in a tiny place 600 kilometres from the capital city.

But the most striking thing about this picture, at least for us, is that the World Bank isn’t in it. Despite our know-how on all kinds of poverty-related issues, that knowledge isn’t available to the millions of people who could use it.

Imagine if it were. Think what an organization we could become.

When Denning began telling people this story, everything changed. Doors opened, he got his funding, his programme was underway.

Anatomy of a story

As Denning investigated other powerful stories, he recognised that this story worked because it had a number of important features.

- A real example - recent, and similar enough to seem relevant

- A single protagonist - someone with whom the audience could identify

- Told simply - no distracting details or particulars that could be quibbled over

- A happy ending - one that showed that change has a payoff

- Handed to the audience - Denning invited them to be part of the story

Keeping it simple

Boiling a story down to its essentials, as Denning had, is hard. You have to let go of so much you think is important.

Denning might have wanted to talk about the Centers for Disease Control’s knowledge management software, its budgets, the scale of its programme. But he recognised one irrelevant fact can be used to question the relevance of the entire story. So he cut everything he could.

Our own stories

We don’t just tell stories to other people. We tell stories to ourselves. Stories are how we make sense of our world.

Think about a story you have about your life right now.

It might be your relationship with a parent - you’re the daughter who can never get it right; or a friend - you’re the good time buddies; or your career - I’m wasted in this job.

Stories like these help us understand who we are, what to do next and why. They help us process new facts. But we’re so attached to our stories that we deny facts that don’t fit.

Stories for change

Shifting people’s behaviour often means helping them to find a new story.

Think back to that COO who buried the user testing report.

She was living within a story. ‘We’ve promised our shareholders that we’ll deliver this project on time - my job is to keep that promise’.

Hers was a powerful story. It was simple, it had integrity, and it was heroic. From her point of view, the she wasn’t the villain burying the truth - she was the heroine helping her team achieve the impossible while others tried to drag them off course.

By presenting her with inconvenient facts, we’d only done half our job. We should have also been working on her story.

What could we have done differently?

We could have started by listening. We were so wrapped up in our story we forgot to acknowledge hers. Would you trust anyone who had a script in which you’re the villain? She had a reasonable story and we should have listened to it.

Then we could have shown we were listening by repeating back what we’d heard. And if we’d asked her how she felt about that story we might have heard about some of the problems her situation put her in, some of the things that didn’t fit the story, and perhaps a discontent with her story.

Next, we could have shown we were on her side. We all wanted her team, her company, and her users to succeed. That would have allowed us to offer her another story - the bigger story where she averted the hasty delivery of a well intentioned, but flawed idea.

Finally, we could have placed our evidence within this new story and built it into her life. We could have talked without judgement about how things got to this state. We could have got her to talk about how the story would play out.

That is not an easy conversation to have. But watching our work being buried was worse.

Staying above the fray

All this talk of crafting stories and changing minds might make you uncomfortable.

Shouldn’t we just remain dispassionate gatherers of information? Shouldn’t we let other people twist facts into stories.

Sounds great. Except it doesn’t work.

By merely reporting facts we are telling a story—badly—and that’s dangerous.

Disaster

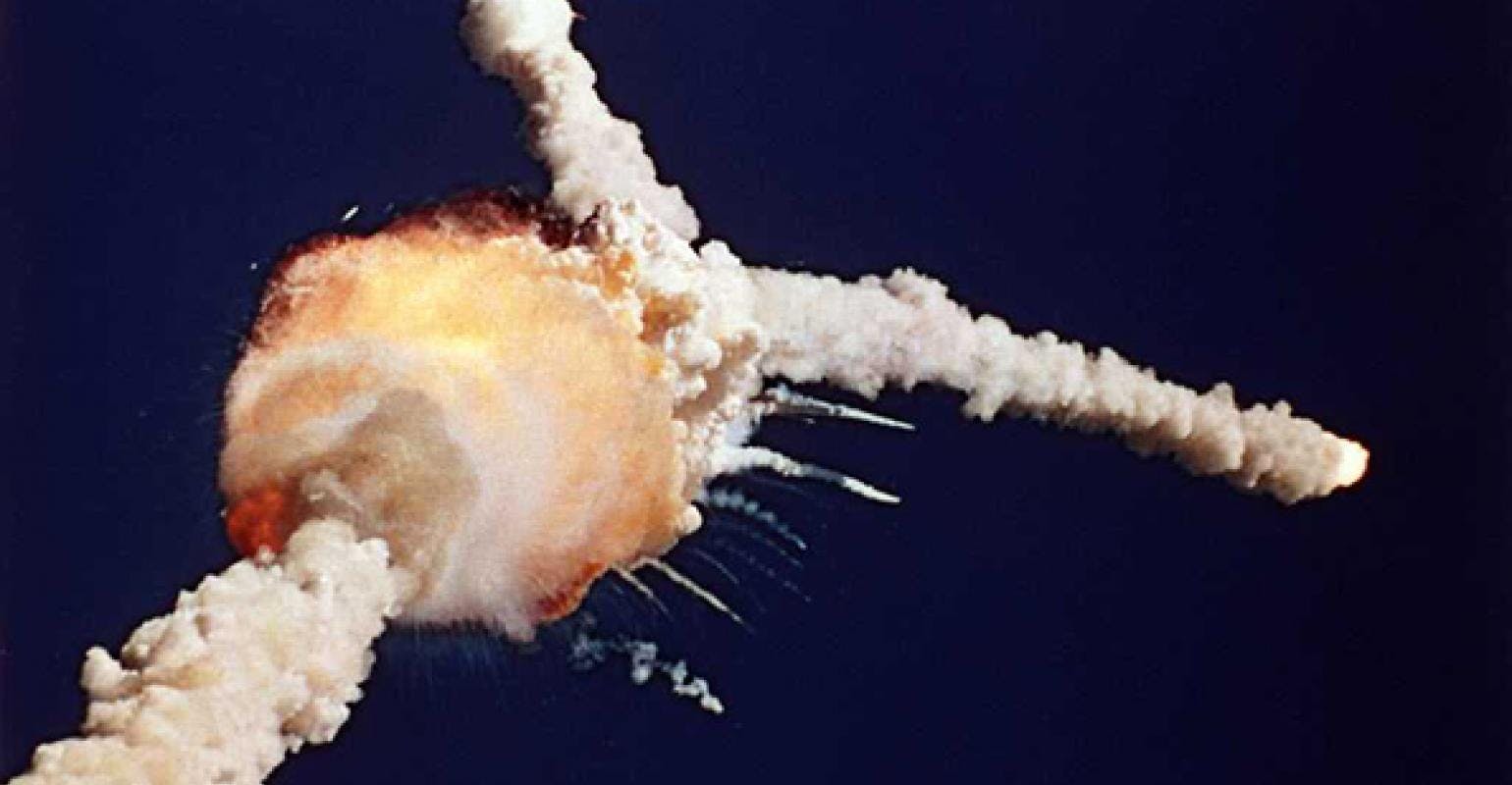

On 28 January 1986 the space shuttle Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after launch.

The cause was later found to be the rubber gaskets used to seal sections of the booster rockets. In the January cold the rubber rings had become stiff and inflexible allowing gas to escape and tear a hole in the main fuel tank, causing the entire spacecraft to disintegrate.

Before launch, engineers had become concerned and sent their data to managers.

But their tables didn’t tell a clear story. Managers were under pressure to avoid delays. They considered the cold to be a marginal factor in deciding to launch rather than a red flag.

By presenting facts, instead of making their data tell a story, the engineers had failed to make their case. ‘Just the facts’ is never enough.

We aren’t separate from the world. We aren’t distant from the difficult decisions. We’re part of them.

Change is our job

Our organisations hire design researchers to have an impact by representing customer needs. That’s our role on the team, our place, our purpose.

The idea that we can be separate and special is just another story we’re telling ourselves. And it’s a dangerous one, because it lets us opt out of the hard work of ensuring that our knowledge is put to good use and that users’ needs are met.

If, like me, you believe this work is important, then you have to have an impact.

A story worth living

Putting our necks on the line is scary. It requires us to take a position, with the risk that we’ll come into conflict. And it requires us to have the humility to accept that we may be wrong, and that our version of the story may not be the best one for everyone right now.

I think it’s important we accept those things. It will be hard. There may be conflict. You may fail.

But you’re never alone in this. You always have team mates, colleagues, allies, and mentors you can talk to. You’ll find strength by sharing the challenge, listening to feedback, and asking for support.

Worst case, you’ll fail, and learn, and go on to do better things. Best case, you get to change the world.

That’s a story worth living.